Make no mistake: “Created Equal” is a one-sided portrait. The film’s director, Michael Pack, is a longtime conservative filmmaker, whose documentaries include “Hollywood vs. Religion” and “Inside the Republican Revolution,” and who led the right-leaning think tank the Claremont Institute for two years. We first met in 2000 when he brought his film “The Fall of Newt Gingrich” to the Maryland Film Festival; in 2017, we engaged in a public conversation at AFI Docs, discussing ideological diversity within the nonfiction filmmaking community. I have remained friendly with Michael and his wife, Gina Cappo Pack (executive producer of “Created Equal”), ever since. Even without knowing the Packs, I would consider “Created Equal” a success, starting with the subtitle. From the outset, viewers are put on notice that the story they’re about to hear is solely from Thomas’s point of view (the only other voice in the film belongs to Thomas’s wife, Virginia). And that makes a difference. Rather than purport to be an objective, journalistic report, “Created Equal” makes it clear that this will be a highly sympathetic account of its subject — a safe space in documentary form. Thus situated, I was able to watch with the appropriate filter, appreciating the fascinating personal and social history that weaves through Thomas’s biography while taking issue with his most frustrating, even infuriating pronouncements. It’s just this kind of compartmentalization — figuring out what you accept, reject, are surprised by or simply want to file away for further study — that defines critical thinking, a skill that has become virtually extinct in a hyper-polarized culture. Can cinema be a depolarizing force? Back when movies were projected in dark rooms full of strangers, we lowered our defenses to enter a kind of shared dream state. That communal experience might be increasingly obsolete, but even taking in Thomas’s story on a laptop forged a far more powerful connection than would have been created by the intellectual exercise of reading his memoir, or an op-ed. You can toss a book across the room, or click away from an article you don’t like; movies are different, in that they operate both as a delivery system for information and as an emotional medium. Even as I mentally picked apart the film’s most objectionable assertions, the ways Pack used Thomas’s voice and the imagery from his past forced me to sit with the man and his story, and to contend with the paradoxical feelings — compassion, admiration, surprise, deep skepticism — that surfaced as a result. I discovered that even passionate disagreement can coexist with edification, however uncomfortably. Of course, film’s ability to short-circuit rationality is precisely what makes it such a potent — and potentially dangerous — medium. But it’s also what makes film an ideal venue for encountering ideas and experiences diametrically opposed to our own. That doesn’t mean that the act of watching a movie is equal to tacit agreement or that buying a ticket confers endorsement. But it does mean entering a good-faith contract between filmmakers, who must be as scrupulously transparent as possible, and audiences, who vow to remain open-minded and critically engaged. When those conditions are met, cinema gives us the best chance possible to lay down our arms, open our minds, and — just maybe — shut up and listen.

– Film Scores –

Listening to Paintings

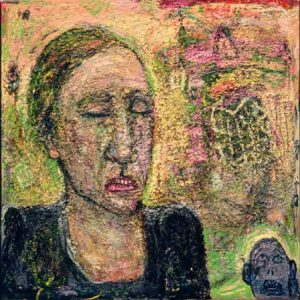

I recently completed the score for a documentary about the dark and quixotic artist Miriam Beerman, who is 91 years old. The film, Miriam Beerman: Expressing the Chaos, is a passion project by the director Jonathan Gruber. It was an incredible challenge to match the intensity of this under-appreciated painter’s vivid canvases while finding a way to illuminate her calm personality. To get this feeling of serenity within chaos, I chose a palette of essentially four instruments; piano, cello, vibes, and percussion—including the high keening sound of bowed crotales.

I recently completed the score for a documentary about the dark and quixotic artist Miriam Beerman, who is 91 years old. The film, Miriam Beerman: Expressing the Chaos, is a passion project by the director Jonathan Gruber. It was an incredible challenge to match the intensity of this under-appreciated painter’s vivid canvases while finding a way to illuminate her calm personality. To get this feeling of serenity within chaos, I chose a palette of essentially four instruments; piano, cello, vibes, and percussion—including the high keening sound of bowed crotales.

Musical for USA Network's "Royal Pains"

Actor/director Paolo Costanzo, who plays Evan R. Lawson on the USA Network series Royal Pains, needed a collaborator to bring to life his vision: a musical production number to cap a five-episode summer 2013 series on the show’s website. Working with composer/arranger/producer Charlie Barnett, Costanzo wrote and filmed “Shine,” a Disney-style musical daydream about a hotly contested village council election.

The sound of printmaking

I recently scored a feature-length documentary on post World War II printmaking in the American Midwest. Somehow, in my mind, Midwest printmaking meant clarinet. And that meant I got the pleasure of recording the principal clarinetist from the Kennedy Center’s opera orchestra, David Jones. What a delight it was working with such a talented multi-instrumentalist. We used clarinet, flute, tenor sax, and bass clarinet in the studio, and David managed to give me every tone color I needed. I could have dug through every synth patch I have to score this and never come up with what that David was able to give me in one beautiful recording session. The film, Midwest Matrix, directed by Susan Goldman, was screened last month in Milwaukee.

Film scoring

There are as many ways to score a film as there are…. well, to write music. We don’t all get to score the big orchestral films we want to on every job. In my case, I bounce around from feature films to TV docs to non-broadcast short films, mostly for corporate clients. This last category is sometimes the most trying. They are usually filled with talk. And you have to remember that this talk is the single most important element to most of these clients. So don’t spend one solitary minute being irritated at all the verbiage in the film. After I once again realize and accept what sort of film I am working on ( Let’s say a 7 minute film for internal use at a rental car company. I have not done that, but it could easily happen) my first step in the process is to figure out WHAT I want to score. My choices seem to boil down to this: Am I scoring the pace of the film only? Am I scoring the tone of the dialog?, Maybe there is a directive from the producer that he wants it to be jazz or country of classical. Usually in films like this you can just forget trying to write an interesting melody. That is generally wasted time. It will fight the precious dialog and do yourself no favors with your producer. That leaves you with harmony and texture to work with. I have found that in most of these films even interesting harmonies can be distracting. So now we’re down to just textures and tempos. That can be fun. I do my best to divide the film up into cues, or acts. It is really important to follow the script. Again, it is the most important element in the film. ( No it is not the music!) The script will tell you, if you are an astute listener, where the different sections are. Once you find those sections the next step is to determine the tempo of each one. After that. You can start writing whatever it is that you think is musically correct for the show- somber, energetic, jazzy, whatever. I have found that the thing that has the most impact in shows like this is hitting cuts. ( in our imaginary rental car film, hitting each of the new models or rental counters or locations etc etc) Having to write to the picture in this way will keep your head in the game. It is way too easy to just loop your way under a bunch of droning voices until you come to the end. The mission sometimes is to keep one’s dignity as a composer while working on things that truly don’t demand much. If you can bring interest an creativity to a film like this, your chops will be honed and ready for the next feature that comes your way. And if all that comes along next is another corporate video, instead of dreading it you will be faster and more effective and probably having more fun.

Hudson River Blues

A feature film aired on The Romance Channel. One of the featured actresses in this film by Nell Cox is Jane Krakowski from 30 Rock. She sings in the film and has an amazing voice. Perhaps I will put that audio clip up sometime soon for her fans to hear.